Table Of Content

Excellent examples of this work (including the study by Hall and his colleagues) can be found in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. A case study is a detailed description of an individual, which can include both qualitative and quantitative analyses. People misunderstand or they misinterpret the term “multiple baseline” to mean that because you are measuring multiple things, that that gives you the experimental control. You have to be demonstrating, instead, that you’ve measured multiple behaviors and that you’ve replicated your treatment effect across those multiple behaviors.

Long-term effect of task-oriented functional electrical stimulation in chronic Guillain Barré syndrome–a single-subject ... - Nature.com

Long-term effect of task-oriented functional electrical stimulation in chronic Guillain Barré syndrome–a single-subject ....

Posted: Mon, 28 Jun 2021 07:00:00 GMT [source]

Multiple baseline

Experimental control is demonstrated when the effects of the intervention are repeatedly and reliably demonstrated within a single participant or across a small number of participants. The way in which the effects are replicated depends on the specific experimental design implemented. For many designs, each time the intervention is implemented (or withdrawn following an initial intervention phase), an opportunity to provide an instance of effect replication is created. One solution to these problems is to use a multiple-baseline design, which is represented in Figure 10.5 “Results of a Generic Multiple-Baseline Study”.

Alternating Treatments and Adapted Alternating Treatments Designs

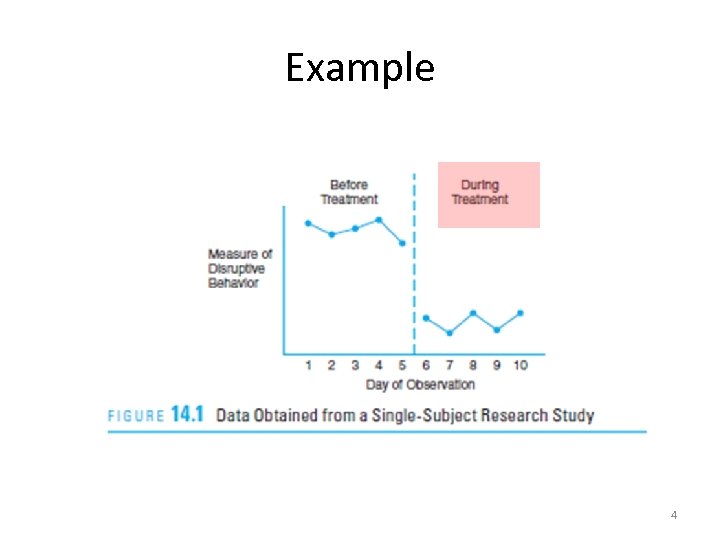

A second factor is trend, which refers to gradual increases or decreases in the dependent variable across observations. A third factor is latency, which is the time it takes for the dependent variable to begin changing after a change in conditions. One of them is changes in the level of the dependent variable from condition to condition. A second factor is trend, which refers to gradual increases or decreases in the dependent variable across observations. A third factor is latency, which is the time it takes for the dependent variable to begin changing after a change in conditions. In yet a third version of the multiple-baseline design, multiple baselines are established for the same participant but in different settings.

Analysis of Effects in SSEDs

Once responding has reached the criterion threshold in the intervention phase of the first leg, continuous measurement of pre-intervention levels is introduced in the second. When stable responding during the intervention phase is observed, intermittent probes can be implemented to demonstrate continued performance, and intervention is introduced in the second leg. This pattern is repeated until the effects of the intervention have been demonstrated across all the conditions. As an example, consider a study by Scott Ross and Robert Horner (Ross & Horner, 2009). One of them is changes in the level of the dependent variable from condition to condition.

2: Single-Subject Research Designs

Once responding is stable in the intervention phase in the first leg, the intervention is introduced in the next leg, and this continues until the AB sequence is complete in all the legs. The most basic single-subject research design is the reversal design, also called the ABA design. A recent example of the withdrawal design was executed by Tincani, Crozier, and Alazetta (2006). They implemented an ABAB design to demonstrate the effects of positive reinforcement for vocalizations within a Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) intervention with school-age children with autism (see Figure 3). A visual analysis of the results reveals large, immediate changes in percentage of vocal approximations emitted by the student each time the independent variable is manipulated, and there are no overlapping data between the baseline and intervention phases. As a result, this case would be considered strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of the intervention based on the WWCH evidence-based practice criteria.

Given the focus of evidence-based practice on clinical decision making for individual patients, these designs are especially useful. Single-subject designs are sometimes confused with within-subject group comparisons or n-of-1 case studies, neither of which usually include multiple implementations of each condition for any one individual. N-of-1 case studies sometimes make no manipulation at all or may make a single comparison (as with an embedded AB design or pre-post observation), which can at best serve as a quasi-experiment (Kazdin and Tuma, 1982). A single subject design, in contrast, will include many repeated condition changes and collect multiple data points inside each condition (as in the ABABABAB design as well as many others, see Perone, 1991). A strong single-subject design will require a minimum of three IV implementations for the same individual (i.e., ABABAB, with multiple data points for each A and each B), and a robust effect will require many more. However, doing so comes at the cost of practitioner flexibility in making phase/condition changes based on patterns in the data (i.e., how the participant is responding).

What Types of Paleontologists Are There?→

Additionally, many clinicians/educators prefer the ABAB design because the investigation ends with a treatment phase rather than the absence of an intervention. Single-subject research, by contrast, relies heavily on a very different approach called visual inspection. Group data are described using statistics such as means, standard deviations, Pearson’s r, and so on to detect general patterns. Single-subject research is a type of quantitative research that involves studying in detail the behavior of each of a small number of participants. Figure 10.4 "An Approximation of the Results for Hall and Colleagues’ Participant Robbie in Their ABAB Reversal Design" approximates the data for Robbie.

This approach, which Skinner called the experimental analysis of behavior—remains an important subfield of psychology and continues to rely almost exclusively on single-subject research. For excellent examples of this work, look at any issue of the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. By the 1960s, many researchers were interested in using this approach to conduct applied research primarily with humans—a subfield now called applied behavior analysis (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968).

Data Analysis

In vivo tractography of human locus coeruleus—relation to 7T resting state fMRI, psychological measures and single ... - Nature.com

In vivo tractography of human locus coeruleus—relation to 7T resting state fMRI, psychological measures and single ....

Posted: Sun, 18 Sep 2022 07:00:00 GMT [source]

Figure 8 shows one participant's correct responses during sessions across baseline phases, alternating treatments phases, and extended treatment phases. There are close relatives of the basic reversal design that allow for the evaluation of more than one treatment. In a multiple-treatment reversal designA single-subject research design in which phases that introduce different treatments are alternated., a baseline phase is followed by separate phases in which different treatments are introduced. For example, a researcher might establish a baseline of studying behavior for a disruptive student (A), then introduce a treatment involving positive attention from the teacher (B), and then switch to a treatment involving mild punishment for not studying (C). The participant could then be returned to a baseline phase before reintroducing each treatment—perhaps in the reverse order as a way of controlling for carryover effects.

Another limitation of group design logic is the practical difficulty of balancing individual differences between groups. In the case of between-group comparisons, these difficulties arise from selection bias, mortality, etc. Even well controlled studies can still produce probabilistically imbalanced groups, especially in the small sample sizes often used in neuroscience research (Button et al., 2013). Deliberately balanced groups or post-hoc statistical control may help, but the former introduces a potential problem with true randomization, and the latter is weaker than true experimental control. The issues are germane because of the WWCH and related efforts to establish standard approaches for evaluating SSED data sets as well as the problem of whether and how to derive standardized effect sizes from SSED data sets for inclusion in quantitative syntheses (i.e., meta-analysis).

This pattern of results strongly suggests that the treatment was not responsible for any changes in the dependent variable—at least not to the extent that single-subject researchers typically hope to see. Single-subject research, by contrast, relies heavily on a very different approach called visual inspection. Group data are described using statistics such as means, standard deviations, correlation coefficients, and so on to detect general patterns. In the top panel of Figure 10.4, there are fairly obvious changes in the level and trend of the dependent variable from condition to condition.

While studies may include more than one subject, each subject is treated as a unique experiment instead of one trial in a larger experiment. ∗These designs have also been called single system strategies,3 N of 1 studies,4 and time series designs.5 Cook and Campbell6 describe time series designs as quasi-experimental ... 1This discussion intentionally excludes assignment to groups based on non-manipulable variables because of the qualitative difference between correlational approaches and true experimental approaches that manipulates the IV. The former carries a very different set of considerations outside the scope of this paper. One of the tools used to help answer the question of “what works” that forms the basis for the evidence in evidence-based practice is meta-analysis—the quantitative synthesis of studies from which standardized and weighted effect sizes can be derived.

The issues related to multiple-treatment interference are also relevant with the ATD because the dependent variable is exposed to each of the independent variables, thus making it impossible to disentangle their independent effects. To ensure that the selected treatment remains effective when implemented alone, a final phase demonstrating the effects of the best treatment is recommended (Holcombe & Wolery, 1994), as was done in the study by Conaghan et al., 1992. Many researchers pair an independent but salient stimulus with each treatment (i.e., room, color of clothing, etc.) to ensure that the participants are able to discriminate which intervention is in effect during each session (McGonigle, Rojahn, Dixon, & Strain, 1987). Nevertheless, outcome behaviors must be readily reversible if differentiation between conditions is to be demonstrated.

First, the time-out component of the intervention was removed, leaving the FCT component alone. A decreasing trend in signing and an increasing trend in hand biting were observed. In the third phase of the component analysis, the FCTcomponent was removed, leaving time-out and differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO). Again, a decreasing trend in signing and an increasing trend in hand biting were observed, which were again reversed when the full treatment package was applied.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of SSEDs specific to evidence-based practice issues in CSD that, in turn, could be used to inform disciplinary research as well as clinical practice. Single subject research design is a type of research methodology characterized by repeated assessment of a particular phenomenon (often a behavior) over time and is generally used to evaluate interventions [2]. Repeated measurement across time differentiates single subject research design from case studies and group designs, as it facilitates the examination of client change in response to an intervention. Although the use of single subject research design has generally been limited to research, it is also appropriate and useful in applied practice. The demands of traditional experimental methods are often seen as barriers to clinical inquiry for several reasons. Because of their rigorous structure, experiments require control groups and large numbers of homogenous subjects, often unavailable in clinical settings.

More broadly speaking, qualitative research focuses on understanding people’s subjective experience by observing behavior and collecting relatively unstructured data (e.g., detailed interviews) and analyzing those data using narrative rather than quantitative techniques. Single-subject research, in contrast, focuses on understanding objective behavior through experimental manipulation and control, collecting highly structured data, and analyzing those data quantitatively. Specifically, the researcher waits until the participant’s behaviour in one condition becomes fairly consistent from observation to observation before changing conditions. First and foremost is the assumption that it is important to focus intensively on the behavior of individual participants. One reason for this is that group research can hide individual differences and generate results that do not represent the behavior of any individual. For example, a treatment that has a positive effect for half the people exposed to it but a negative effect for the other half would, on average, appear to have no effect at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment